Understanding the geolocation element

A couple of weeks back, Chrome detailed its new <geolocation> HTML element that shipped in Chrome 144. Intrigued, I read through the post wondering what magic lay within. But it didn’t seem like anything new. There was nothing this new element could do that JavaScript couldn’t do already.

So what’s the point? Why go to such great lengths to introduce a new HTML element to do something we have been able to do for over 15 years?

The problem

Websites are annoying. Not my websites, obviously. But I’m sure we’ve all been to one that immediately hits you with one - or a few - of these:

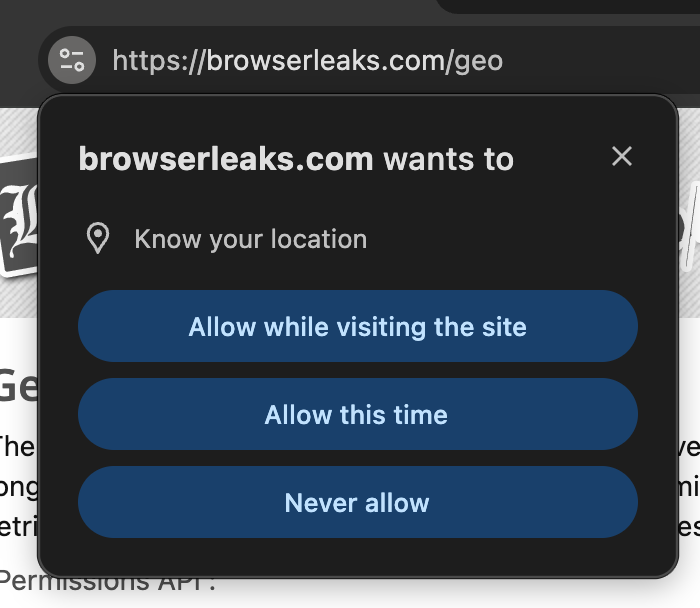

You’ve barely started reading before you’re asked to share some quite personal information. There’s no obvious trigger, you’ve got no idea what they will use it for and you immediately dismiss it. It’s incredibly annoying.

That’s a problem for the website too. If you never allow permission again, it’s got nowhere to go. The steps required to re-enable those permissions are complicated and vary by browser. Browsers have resorted to shadow-banning requests from sites they deem to be abusing those requests, leading to broken experiences.

An API like window.geolocation is imperative: it tells the browser to do something but without providing context or knowing that’s what the user intended. It’s hard to identify what triggered it in the first place.

The history

There have been ongoing efforts towards a <permission> element for a couple of years by this point. Browsers needed a way to know that the user has provided some active intent before access to a powerful feature like geolocation could be given.

The idea was simple. Provide a generic element that allows a site to present its intentions declaratively. You provide a type e.g. <permission type="camera" /> and the browser renders a button on the page to trigger that permission. Clicking that button triggers a permission request and from there a range of callbacks keep the page aware of what the user has allowed.

Sounds fine in practice, right? Browser vendors weren’t so keen.

It turns out it’s not so straightforward. Different features that require permissions require different levels of acceptance from a user. A catch-all element like this would end up getting complex enough that it would be difficult to use.

The solution

In an effort to be more targeted, the Google team decided to move to <geolocation> - a more specialised element that could tackle its particular problems in its own way. It focuses more on sharing location information, rather than simply requesting permission.

It takes a few attributes that expose all the same useful information as the JavaScript API:

<geolocation

onlocation="handleLocation(event)"

autolocate

accuracymode="precise"

>

</geolocation>

It emits a location event when access is granted, providing all the information you need. You can provide attributes to control the level of access you have, such as how accurate the location is or for movement tracking.

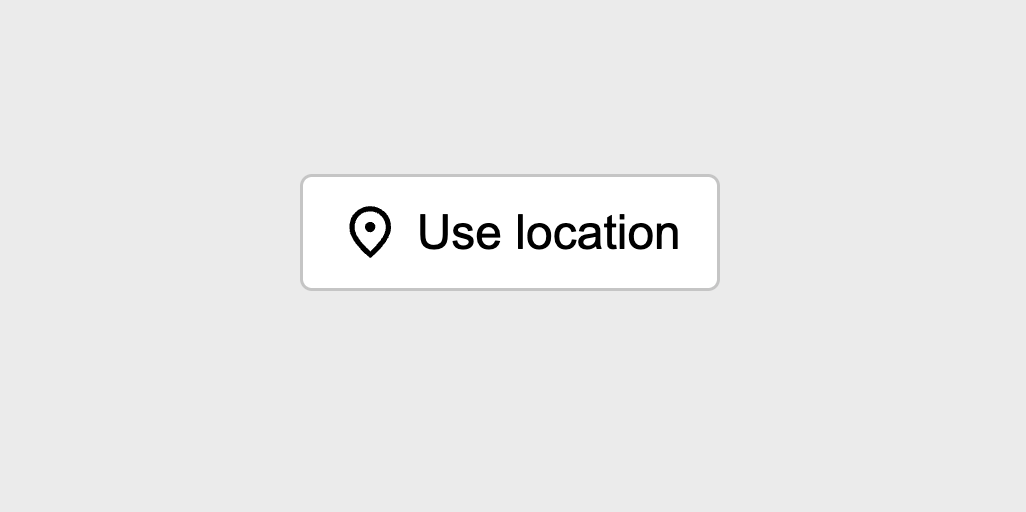

In Chrome, it renders like any other button:

This can be added anywhere in the page it makes sense. For example, you could add it as part of a weather widget to offer users more accurate information should they wish to opt in.

The control itself has a standardised look and feel. Each browser will supply one that fits their look and feel but with some limits on how you can style to match your site. For example, you can’t just make a giant transparent one that covers the whole window. They’ll see right through that one - ironically.

While the styling itself may be limited, it does become aware of permission state. It can be styled to show when permission is granted or denied to provide clearer feedback to users without the reliance on JavaScript.

It can be progressively enhanced too. Any browsers that don’t understand what a <geolocation> element does will show whatever’s inside of it. You can hide some fallback behaviour in there, such as using the JavaScript API instead.

The benefit

If, like me, you’re sitting there going “OK, but why?” then you’re not alone. It seems like they’ve gone out of their way to make something new with no immediately obvious benefit.

A lot of the online discourse agrees. The benefits aren’t immediately clear, but there are a few.

- It’s declarative. Markup makes the intent explicit to both users and browsers. Fewer safeguards are needed.

- It’s accessible. Semantics are clearly defined and readily exposed to screen-readers. Developers are limited in what they can do to disrupt this.

- It’s secure. Permissions are granted only after clear user intent, and only while the element remains visible. Remove the element and access is revoked.

- It’s efficient. Removing the element will remove all the listeners and tracking behaviours along with it, which is not always done when accessed through JavaScript.

- It’s SSR friendly. A standardised approach makes it easier to parse, lint and analyse compared to arbitrary JavaScript calls.

Jeremy Keith put it best in the latest ShopTalk show episode. The HTML version doesn’t need to do everything, it just needs to do 80% of the most common use-cases well. The JavaScript version is still going to be there for those more niche situations. Everyone else can benefit from a more unified, predictable experience.

The future

This remains a Chrome-only thing for now.

Chrome itself doesn’t have a stunning track record for self-nominated HTML elements. However in this case it’s gone through the standards process, garnered feedback from major players and iterated in public on the idea until everyone’s happy with the results.

The signals from Firefox are broadly positive now it’s a more specific element. Right now Safari/WebKit has its reservations, but it’s open to discussions.

I think it will be another little while until this becomes a cross-browser kind of deal. But it’s easily polyfillable, backward compatible and in the meantime provides value to all kinds of users. I can’t see why you wouldn’t at least consider use it.